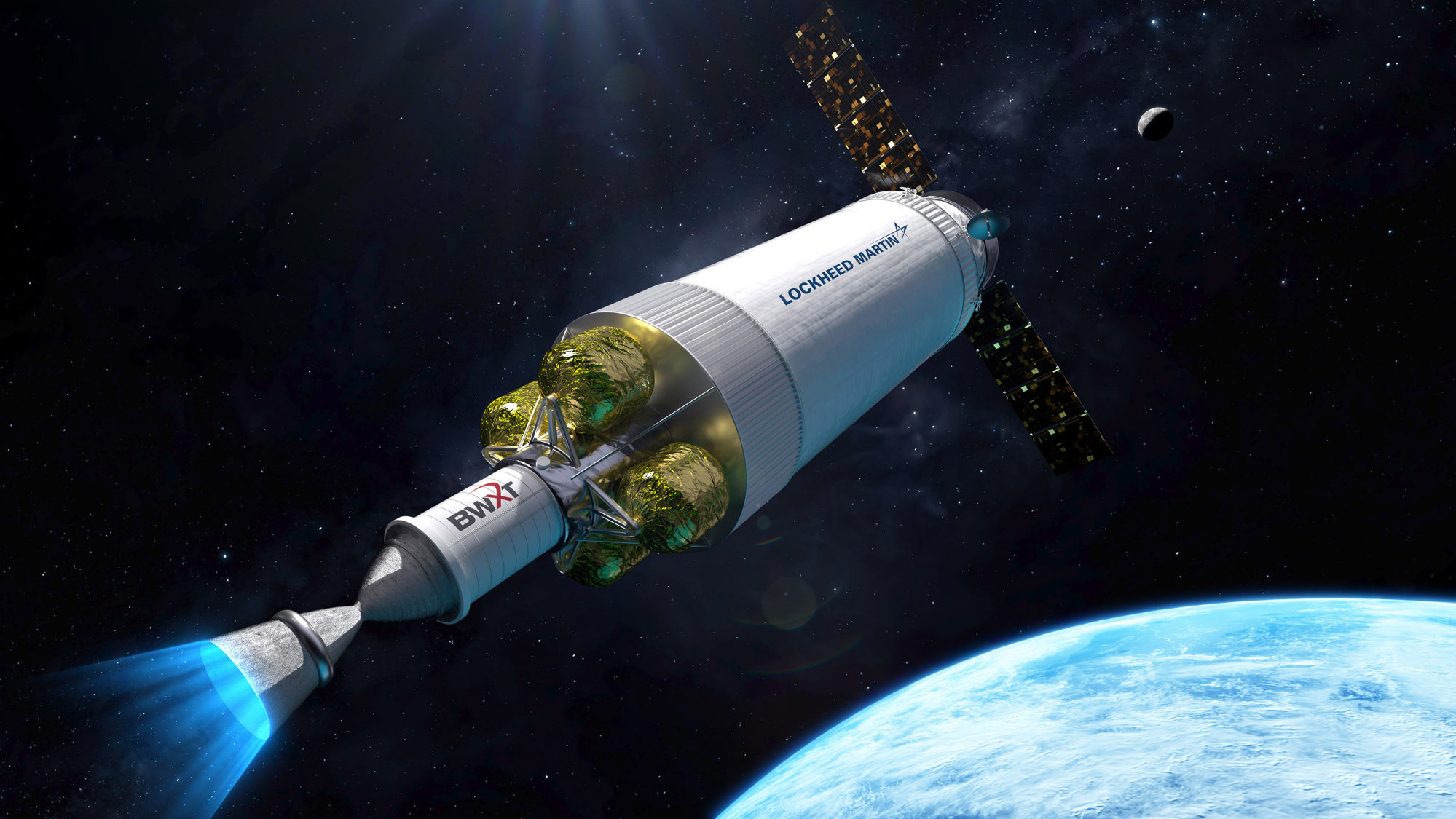

Lockheed Martin picked to build US nuclear-powered spacecraft

- US goal will be to launch a spacecraft with a nuclear engine in 2027

- Nuclear spacecraft could make trips to the moon and Mars more efficient

A US Department of Defence agency and Nasa selected Lockheed Martin Corp to design and develop the first nuclear thermal rocket engine to be tested in space, part of a programme called DRACO.

Through a contract announced on Wednesday with the federal research and development organisation known as DARPA, Lockheed Martin will design and build the nuclear-propelled engine along with an experimental spacecraft, called X-NTRV. The goal will be to launch the spacecraft with the nuclear engine in 2027.

The overall value of the contract is roughly US$500 million, with Nasa committing about US$250 million and DARPA contributing the rest.

The space agency is primarily focused on funding the engine development, while DARPA will handle the nuclear regulatory requirements and environmental protocols surrounding the launch. The US Space Force will provide the launch vehicle and pad for the X-NTRV vehicle.

The idea of nuclear thermal propulsion has long been considered as a way to send shortened crewed missions to Mars. Such engines could produce high thrust, but more efficiently and with less complexity than traditional chemically powered rocket engines.

Nuclear-powered rocket engines work by transferring heat from a reactor to hydrogen propellant. As the hydrogen heats up, it expands and is funnelled out of a nozzle, producing thrust.

Though Lockheed Martin will create the engine, Virginia-based BWX Technologies will build the nuclear fission reactor for the engine. The Department of Energy will also contribute high-assay low-enriched uranium (HALEU) fuel for the reactor.

To date, there has been no in-space demonstration of nuclear thermal propulsion. In the 1960s and 70s, Nasa conducted a programme called NERVA, which aimed to develop a nuclear-powered rocket engine for deep-space missions, though nothing ever flew in space.

Through the programme, scientists developed 23 thermal nuclear reactors and engines. In January, Nasa and DARPA announced their plans to collaborate on DRACO to perform an in-space demonstration of the technology.

DARPA noted that testing this engine on the ground is not currently possible. “There are no facilities available to accommodate the assortment of experiments needed to get the reactor to a high enough power level,” Tabitha Dodson, programme manager for the DRACO programme at DARPA, said during a press conference. She also noted that the old NERVA test site cannot be used because it has been mothballed and policies have changed since the site was used.

An operational failure during launch or in space could present the risk of spreading radioactive material. “The reactor will not be turned on until the spacecraft has reached a nuclear safe orbit,” Lockheed Martin said in a statement, making the system “very safe”.

“A reactor that has never been turned on is cold and benign,” Dodson said. “You can put your hand right inside the core and touch the fuel like you would any other heavy metal.”

DRACO’s orbit will be somewhere between 700 and 2,000km (435 to 1,243 miles), according to Dodson, citing international standards for what is considered “nuclear safe.” The demonstration should last a few months, and then the spacecraft may remain in orbit for hundreds or even thousands of years, depending on the altitude DARPA and Nasa decide upon.

One primary safety concern surrounding DRACO is the possibility of a launch failure that plunges the spacecraft into the ocean, since water could mingle with the reactor and cause it to critically malfunction.

Representatives for BWX Technologies said they’ll install “poison wires and poison systems” that would prevent the reactor from becoming a major hazard if it hit water.